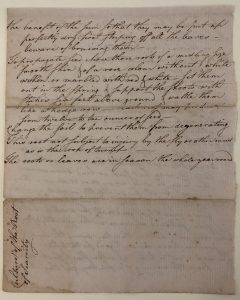

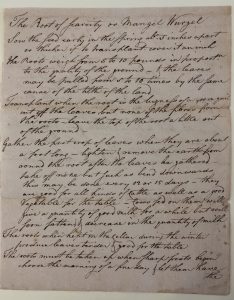

“Nonplus.” The Daily Tar Heel, November 28, 1950. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/70899507/?terms=carolina%2Binn%2Bfood

This primary source is from The Daily Tar Heel was written in 1950 and discusses the differences between many different restaurants in Chapel Hill. Many students that went to UNC had to eat out and pay the price for it. During the war efforts Lenoir Dining Hall was closed for Navy use only, this forced students to eat at restaurants near the university. Seeing that the students had to eat off campus many restaurants raised their prices because they knew students would still have to eat at their restaurant. [1] Many of these restaurants are still around today and some are not. In the article it talks two nicer restaurants one being The Carolina Inn. The Inn is a notorious hotel and restaurant in Chapel Hill that opened in the 1924 and is still very well known today. The Inn was originally owned by John Sprunt Hill, but he gifted the Inn to UNC. The money from the Inn today supports the North Carolina Collection at the Wilson Library. [2] The article discusses how the restaurant at the Inn was very elegant and was known as a four-star restaurant. The prices of a full meal at the Inn was $1.40, which was something many students couldn’t afford. This is very different from today because you probably couldn’t get a glass of water with that amount of money at the restaurant today. The restaurant and Inn are still very well known as an elegant place to eat in Chapel Hill, and known for its exceptional food.

This object presents the War and Postwar time in a lightening manner. Discussing restaurants that students ate at in Chapel Hill. It presets how the war time was hard for everyone including students with high restaurant prices and not being able to eat at the Dining Hall. Furthermore, this illustrates how well known and impactful The Carolina Inn has had in Chapel Hill since it has been open.

[1] Hysmith, KC. “Names in Brick and Stone: Histories from UNC’s Built Landscape.” Names in Brick and Stone: Histories from UNC’s Built Landscape, unchistory.web.unc.edu/building-narratives/lenoir-dining-hall/#_edn20.

[2] “About the Inn.” The Carolina Inn – Crossroads Chapel Hill Restaurant Menu, www.carolinainn.com/about-historic-carolina-inn.

-Sarah Mitchell